Food and eating are deeply personal areas where young people, particularly PDAers, have a natural sense of needing some control to feel secure. This makes it essential for us to respect their autonomy. Our role is to support them by creating positive, pressure-free food opportunities that foster curiosity, enjoyment, and trust, while meeting their unique needs and preferences.

I like to use the word ‘opportunity’ when referring to providing food. The Webster’s Dictionary definition of ‘opportunity’ is that it refers to the chance or favorable conditions provided to enable someone to do something.

In the context of eating, it means creating an environment where a person feels safe, supported and encouraged to explore and engage with food at their own pace, without pressure.

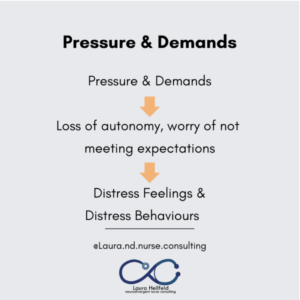

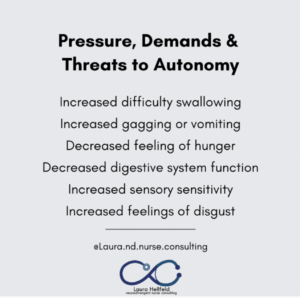

This approach is especially crucial for PDAers, as providing food opportunities rather than imposing demands helps avoid triggering the stress response. Pressure to eat or conform can activate feelings of overwhelm and a loss of autonomy, escalating distress and resistance.

How the Body Responds to Stress & Pressure

Stress and pressure trigger very real physiological changes in the body, activating what is often called the ‘Fight, Flight and Freeze’ responses. These changes are automatic and often unconscious, driven by the nervous system’s attempt to protect us from perceived danger. A few examples of this are how we experience an elevated heart rate, rapid breathing, muscle tension and even shutdown behaviors when our body prioritizes survival.

How Does this Relate to Food & Eating?

When your young person perceives a threat or is in distress, they experience physiological changes that greatly impact being able to eat and food choices.

All of these physical reactions make it incredibly difficult for your young person to feel capable of eating. As you can imagine, they are more likely to now skip eating, eat less or rely more heavily on their same foods in order to find safety and comfort.

Looking Even Deeper

Lesser Known Stress Responses with Eating

Thanks to the work of PDA advocates like Kristy Forbes & Sally Cat, we have an expanded knowledge of distress responses that PDAers are known to have in response to demands.

These are in addition to fight, flight & freeze & are often referred to as secondary distress responses. Some people who helped develop knowledge of these are Dr. Stephen Porges, Peter A Levine, Bessel van der Kolk and Pete Walker.

Fantasy distress behavior: refers to a stress response where an individual retreats into imagination, daydreaming, or make-believe scenarios as a way to escape or cope with overwhelming situations. This response is often automatic and unconscious, providing temporary relief from distressing emotions or environments.

Fib distress behavior: refers to a stress response where an individual tells small lies or fabricates information, often automatically and unconsciously, as a way to avoid conflict, fear or further distress. This behaviour is typically a protective mechanism rather than intentional deceit.

Forget distress behavior: refers to a stress response where an individual appears to forget or lose track of tasks, information, or responsibilities due to overwhelm or distress. This response is often automatic and unconscious, reflecting the brain’s way of coping with stress by prioritising immediate survival over memory or focus.

Fawn distress behavior: refers to a stress response where an individual attempts to appease or please others to avoid conflict, danger or further distress. It is often automatic and unconscious, driven by a need for safety. It can involve excessive agreeableness, compliance, or self-sacrifice at the expense of personal needs or boundaries.

Funster distress behavior: refers to a stress response where an individual uses humour, playfulness or entertainment as a way to cope with or diffuse a stressful situation. This behaviour is often automatic and unconscious, serving as a mechanism to seek safety, connection or distraction during moments of distress.

Flop distress behavior: refers to a form of shutdown or passive response in individuals, often as a result of overwhelm, stress, or sensory overload. It typically involves the person ‘flopping’ to the ground, sitting, or lying down and becoming unresponsive or minimally responsive. This behaviour is a way of coping with a situation that feels too intense or unmanageable. This is a non-verbal expression of distress rather than defiance.

Did you catch one of the patterns in this list? The distress response being unconscious and automatic

How Can We See Secondary Stress Responses During Eating?

These will be exemplified in relation to a PDAer being told by a parent that in order to be done with lunch, that they need to eat a strawberry.

(In my head, I can’t help but liken this to the stories of If You Gave a Mouse A Cookie, and so this is like the story of If You Gave a PDAer a Strawberry)

Fantasy – ‘But I am a cat and cats don’t like strawberries!’

You can read a bit more about PDAers and fantasy (and cat culture!) in my blog ‘Getting to Know PDAers’, found on my webpage or as a free PDF here.

Image from Canva, by Nils Jacobi from Getty Images

Fib – ‘I already did! You missed it ‘cause I was so quick.’ (as they wrap the strawberry in a napkin to throw away later)

Forget – ‘I didn’t remember you said that and I’ve already had too many crackers and will get sick if I try to eat that strawberry. You don’t want me to get poorly, do you?’

Fawn – ‘Oh Mummy, the sandwich you made was so good and I ate all of the bites and now I am so full.’

Funster – ‘Look at my strawberry eyes!’ as they hold the strawberries up to their face and then ‘Oh! I have strawberry hair! Haha!’

Image from Canva, by Luiza Nalimova from Getty Images

Flop – similar to freeze, the young person may throw themselves on a nearby sofa & appear so tired & weak that surely they cannot get up to eat that strawberry or respond to the parent calling for them.

These are all super clever ways the young person uses to protect themselves and try to avoid the demand of eating the strawberry.

The PDAer responded in ways to maintain a sense of control over what foods they would accept to eat. Losses in autonomy therefore make it difficult for someone to eat or accept food. What you might have noticed is, that sometimes, it’s not about the strawberry but rather how the strawberry was presented. PDAers want and need to be in control during food opportunities.

What Can Help?

Recognizing these Reactions as Natural and Involuntary: This helps us to respond with understanding and compassion.

Low Pressured Food Opportunities: These are the key to helping your young person eat or consider expanding into eating new or different foods.

Offer Choices Without Pressure: Provide a variety of foods and let the young person decide what, how much or whether to eat. Avoid comments about their choices.

Create Food Opportunities Outside Mealtimes: Place snacks or small portions of food in accessible areas where they can choose to engage with them independently.

Separate Food from Expectations: Focus on enjoying time together rather than on what or how much is eaten.

Neutral Food Presentation: Serve food neutrally, without making it seem like a reward or punishment.

Include Familiar and Same Foods: Always include at least one food the young person is comfortable with if any new or less familiar options are also presented. Your young person may prefer for any new foods to not be presented on the same plate as their familiar foods.

Engage Without Pressure: Support the young person to explore food through touch, smell, or play without any expectation of eating it.

Serve Food in a Relaxed Setting: Use settings where the young person feels comfortable and unpressured, such as a picnic or eating while doing a favourite activity.

Serve Food Family or Buffet-Style: Serving food in dishes separate from their own to support them making choices and also learning about portions.

Use Shared Activities: Involve them in cooking or food prep in a way that feels fun and empowering, without the expectation that they’ll eat the result.

Respect Their Autonomy: A ‘no’ or not wanting any more food can be for many reasons. Refrain from insisting on clearing plates.

Avoid Time Constraints: Allow meals and snacks to be flexible in timing and duration to suit their needs.

Normalise Preferences: Reassure them that it’s okay to have food preferences and dislikes, and avoid labelling foods as “good” or “bad”

Be Mindful of Language: Use neutral language about food and eating, avoiding phrases that might imply judgment or create pressure.

Create Food Opportunities Outside Mealtimes: Place snacks or small portions of food in accessible areas where they can choose to engage with them independently.

References and Signposting

Laura is an PDA Autistic and ADHD health educator, independent Nurse & Sleep Consultant, and Associate Editor of Autistic Revolution magazine, specializing in supporting neurodivergent and disabled community members.

Drawing from lived experience and public health service, Laura creates inclusive spaces, hosts community events and co-authors books like Gabby’s Glimmers and Creating Safe Spaces for Autistic People.

Laura’s Newsletter on Substack