By SallyCat, Adult PDAer & Author of PDA by PDAers

Masking means hiding your true feelings by having a contrary expression on your face. Physical signs, such as posture, can be masked as well. For example, people can mask feeling upset by holding back their tears and pulling their lips into a smile. Another example is a neurotypical male hiding pain so he appears tough.

Anyone who has interacted with the autism community, even for a short time, will be aware that masking is considered a wholly evil, unhealthy and painful practice that can, and should be, dropped.

This confused me when I first began to explore my own autism after my adult diagnosis in 2013. I’d sought this diagnosis after seeing masking and social mimicry described in a female autism traits list. These were things I’d always done without thinking about them. I was perplexed when, after joining an online autism forum, that masking was talked of as something non-autistic people wanted us to do but that autistic people didn’t want to do themselves.

I’ve since devoted hundreds of hours of online chatting, self-reflection and even peer research into making sense of why masking feels natural to me (in fact, trying to drop it is painful and exhausting) but perceived in an opposite way by the autism community at large.

I now know that many autistic children are subjected to ABA and other behavior based “therapies” that force them to suppress their natural selves and causes long-term psychological damage, including PTSD and tics.

I’ve also learnt that there are other autistic people who experience their masking as something natural that they can’t drop. Many of these fellow natural maskers are, like me, PDA.

There appear to be at least three different types of masking, of which only one is the harmful type. Other forms of masking are adaptive communication and pain-masking behavior, both of which are instinctive.

Although all types of masking look similar externally, they’re caused by markedly different internal processes. Distinguishing the type of masking reveals whether it should be avoided, accommodated or utilized.

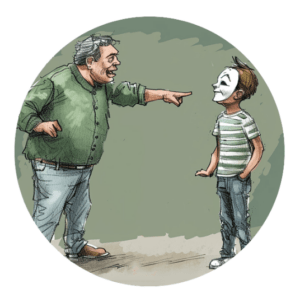

Imposed masking

This is the highly damaging form of masking that the autism community has in mind when they say masking can, and should be dropped. It involves suppressing natural neurodivergent traits, regardless of the cost to the individual, because someone else demands it.

Imposed masking is a key feature of ABA “therapy”, which autistic children are frequently subjected to, and is especially common in the United States. ABA uses the same basic methods that an experimental neurologist, named Pavlov, pioneered to program dogs to drool whenever he rang a bell. Similarly, children subjected to ABA are conditioned to make eye contact and suppress hand flapping, spinning and other physical actions necessary for them to self-regulate. As noted, the resulting trauma of ABA has been shown to cause post traumatic stress disorder.

Forcing neurodivergent children, or adults, to mask sets them up for a lifetime of ceding their needs, mental health and identity to others. This is quite probably one of the reasons that neurodivergent people are prone to being in abusive relationships.

Adaptive communication

Adaptive communication refers to actively changing how we speak, what body language we use, and even what we wear to enhance the effectiveness of our social intercourse. There’s often, if not always, an accompanying desire to put whoever’s listening to us at ease.

Examples of adaptive communication are speaking and dressing formally when in formal company, and exaggerating a local accent to match the way another person talks. The motivation is to improve communication by putting the other party at ease and making it easier for them to grasp what we’re saying. This benefits us too because it makes the other person more likely to respond in the way that we want. This might be as simple as to have them accept us into their group (for example, if watching a sports match in a bar) or it could involve a more material benefit, such as being successful in a job interview.

Adaptive communication differs from imposed masking because:

- It benefits the person who masks

- We’re not forced to do it

- It isn’t painful to carry out

A key component of adaptive communication is social mimicry, which means copying tone of voice, posture and mannerisms. Social mimicry is an unconscious human instinct which increases in intensity the more a person believes themself to be different from the social norm.

As for social mimicry, adaptive communication is an instinctive social strategy that’s used by all people, bar some autistic people. After all, autism cannot be diagnosed unless a social communication difference is present. It seems likely that one of these qualifying social communication differences is having no instinctive drive to adapt communication. This would explain why autistic people face so much societal pressure to mask.

There appears to be a parallel between adaptive communication and the instinctive submissive behavior that strong animals use to pre-empt conflict by appearing non-threatening, friendly and playful (think of a dog rolling on its back and wagging its tail). In comparison, imposed masking can be thought of using a whip to train a lion to jump through hoops.

Pain masking

The term “pain-masking behavior” was first used to describe prey animals’ protective evolutionary instinct to hide signs of injury and pain in order to avoid being targeted by predators.

The term “pain-masking behavior” was first used to describe prey animals’ protective evolutionary instinct to hide signs of injury and pain in order to avoid being targeted by predators.

Although no formal studies have been carried out, many PDA kids, and adults, seem to instinctively hide their pain and vulnerability too. PDA comes with being highly prone to having our adrenal glands triggered so we go into fight, flight, freeze or a more complex defense strategy, such as using pain masking to hide our vulnerability from would be attackers.

It should be noted that human pain-masking isn’t exclusive to PDA people and is carried out, for example, by other autistics. When this is the case, pain-masking may be the result of acquired trauma. With PDA, however, our inherently high anxiety causes us to be like this naturally. I’m planning to explain this is more depth in different blog article about PDA and F adrenal responses.

An example of pain masking is a child having a painful accident, but remaining perfectly still, and showing no hint of distress in their facial expression.

Pain masking and internalized PDA

As the nature of pain-masking behavior is to instinctively contain pain and distress within a calm facade, it appears to be the driver behind internalized PDA, which is characterized by containing meltdowns and other strong emotions so we appear calm and unflustered to observers.

There has been increasing interest in internalized PDA as more and more adults hear of PDA and, upon exploring it, realize they match all the core traits (irrational demand avoidance, high anxiety and control need, liking novelty, having social communication issues and being drawn to people) except for having freely expression meltdowns.

It seems that the masking element of internalized PDA has hidden it from the notice of the researchers and theorists who first noticed our condition. Now that awareness of PDA is growing, those of us with quieter profiles are able to self-identify and add our lived experiences to the knowledge pool.

Situational mutism

Situational mutism, sometimes termed “selective mutism”, means being completely quiet and unmoving during certain social situations, such as in school, but not in others. It can be thought of as a form of pain-masking because, as well as being mute, it causes us to have frozen, rigid facial expressions and be desperate not to stand out.

Situational mutism, sometimes termed “selective mutism”, means being completely quiet and unmoving during certain social situations, such as in school, but not in others. It can be thought of as a form of pain-masking because, as well as being mute, it causes us to have frozen, rigid facial expressions and be desperate not to stand out.

It sets in after toddlerhood and tends to show up after children are compelled to interact with people outside their close family circle, for example, when they start going to childcare or kindergarten.

It seems to be very common for PDA kids, and, I can tell you first hand, is also experienced by some PDA adults.

Situational muteness varies in intensity. A child might be able to talk in front of their class, but not one on one to individual classmates.

Spare play

Spare play is where a child skips about the schoolyard so it looks like they’re playing with others, but close observation reveals that they’re not interacting with anyone else at all.

The term “Spare games” was coined by a nine-year-old client of an expert speech and language consultant, Libby Hill, who specializes in PDA and situational mutism and says she’s since met many other PDA, and general autistic children, who also do this.

Some of Libby’s young, spare-gaming clients told her they preferred playing alone, but others said they wished they could play with their classmates. Both myself and my daughter have spare-played. However, whilst I, as a child, hated feeling like a social failure and was depressed and ashamed to be shunned in the school playground, my daughter complained that her classmates pestered her to play, and said she preferred playing alone.

I can clearly remember being aged about seven or eight and having the energy to play in the schoolyard, but no one to play with because I couldn’t connect with my peers. I switched into my latest immersive daydream scenario, which involved me living in a wooden hut in a forest with tame fawns, and skipping around acting it out.

Even if a child wishes to play solo, spare-playing is used to mask social isolation. If we remember that “pain-masking” behavior is an evolutionary strategy to conceal weakness from predators, spare-playing serves that purpose. After all, lone prey animals are easier to pick off than ones in the middle of a herd. Of course, spare-playing children aren’t protecting themselves from the eyes of prowling lions, but the instinct doesn’t differentiate.

An important consideration with spare-play is that many teachers, special education needs coordinators (SENcos) and visiting assessors don’t know to look out for it and can assume the child in question has no social difficulties because they appear to be playing with their peers.The trick is to keep on watching the child. If they’re spare-playing, it soon becomes clear that they’re not interacting with their peers at all.

Conclusion

Although human masking is often thought of as an autistic thing, the reality seems to be that all people naturally mask except, perhaps, for the beleaguered group of autistics who keep being told to mask and, understandably, don’t want to because doing so is painful and traumatic.

To my mind, not only is it never OK to force someone to mask their authentic selves, it’s also not good to presume that all masking is something that’s forced and harmful. This is a concept I’ve struggle to communicate to the autistic community at large, where masking is viewed with collective hatred. However, at this precise same time, others rally round saying, “Hey, I automatically mask too, and it doesn’t hurt me unless I try to stop doing it.”

There’s clearly a lot more complexity and variety to masking than can be seen on the surface which, let’s face it, is very little because, hey, we’re talking about masking.

As always with PDA and neurodivergence in general, more research is needed.

As it stands, we’re the equivalent of early pioneers exploring a largely unknown continent with the aid of an inaccurate, best guess map that’s labeled with things like “here be dragons”.